How is a unicorn made?

A primer on $1 billion dollar unicorns

Welcome back to MoneyLemma! The topic this week is unicorns, companies that become worth $1 billion dollars. The idea for this post is inspired by a video on the Company Insights YouTube channel, which does awesome 15-minute deep dives on unusual companies. Topics of this post include defining a unicorn, how unicorns are made, and why there were less than 5 unicorns made in 2006 and 142 in 2019.

What is a unicorn?

Each year there are approximately 700,000 new businesses launched in the United States. 20% fail within a year. 45% fail within five years. The lucky ones actually turn into viable, profitable businesses. The exceptional ones, the unicorns, become billion-dollar companies. Even in 2020, the most successful year for new unicorns ever, there was a less than 0.01% chance of any company becoming a unicorn.

The unicorn club has two rules. First, to be worth $1 billion dollars a company has to be sold at a $1 billion-dollar valuation. Valuation means that the total company value is imputed based on a fractional sale. For example, in October 2018 Allbirds joined the Unicorn club when it sold a ~3% stake for $50 million. That implies a 100% stake would be worth about $1.5 billion - unicorn territory. Most unicorns are created this way, with no transfer of majority ownership. That the company must be sold might seem an unnecessary criteria, but it’s important. Appraisals don’t count. Pawn Stars can’t ballpark the value of a vegan waffle company. The unicorn club needs proof of membership, otherwise any company could proclaim itself a unicorn and the world would descend into madness.

Second, unicorns are privately-owned companies. Any company that lists on a stock exchange forfeits unicorn club membership. Unicorns often are described as start-ups. Start-ups are...hold on...wait...surely there’s a definition somewhere on the internet. Oh wait, there isn’t. One would be hard-pressed to find a less meaningful piece of business jargon, and competition is stiff - this is the industry that brought you “it is what it is” and “if I can be honest with you.” Start-ups are companies trying to make lots of money, which is to say, all companies. Facebook just crossed $1 trillion in value and there’s still articles like this one: Why Facebook is Still a Startup. Unicorns don’t have to be start-ups, they just have to be private companies.

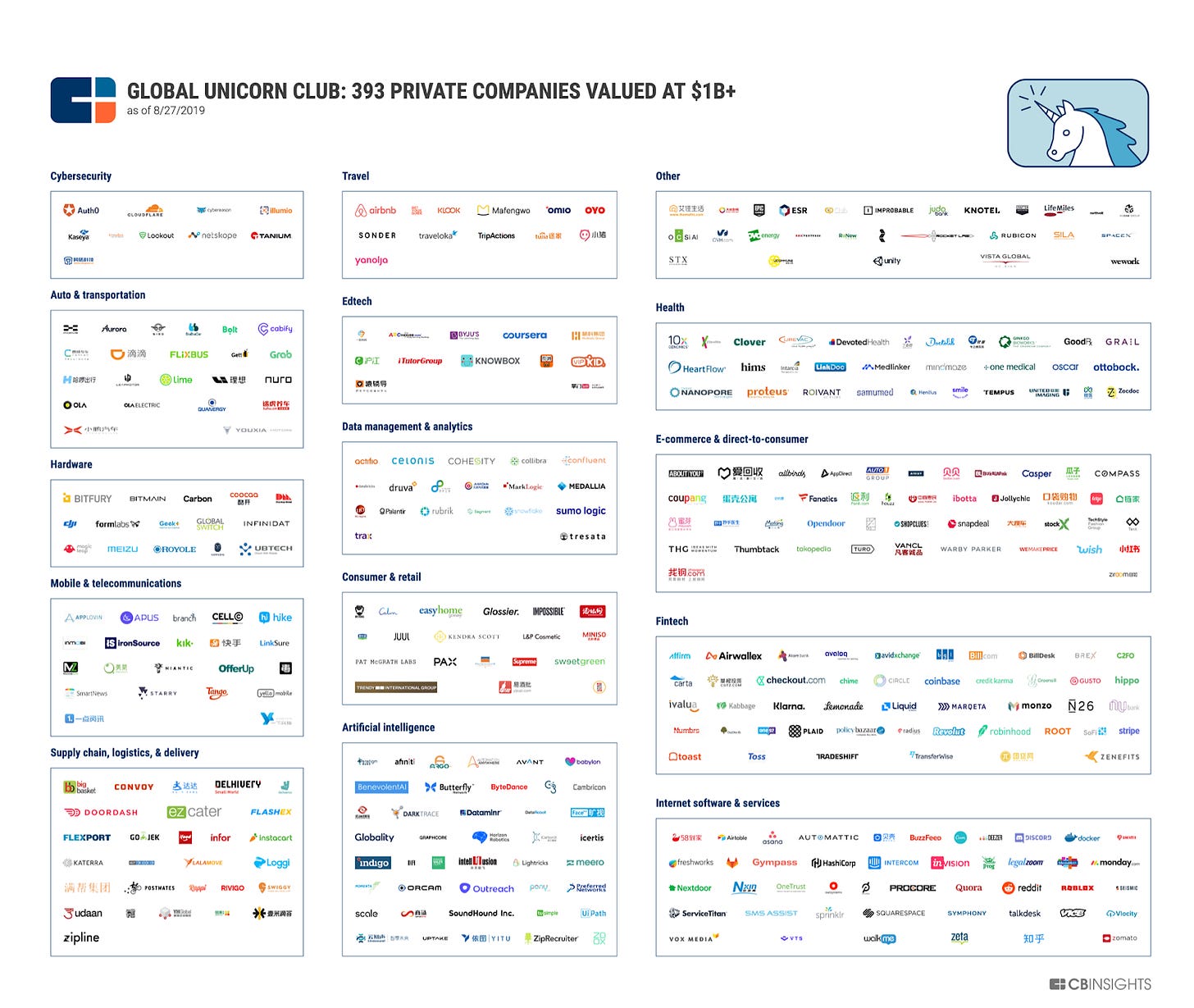

CB Insights is an authority on unicorns. They map the unicorn genome, delicately dissect the magical creatures the way Gregor Mandel sexed peapods. Here’s their latest unicorn taxonomy:

The watchful eye may notice something. There are like, a thousand companies missing from this list. Here’s an easy one: IKEA. IKEA is a private company with revenue of about $50 billion. Unfortunately, IKEA doesn’t meet rule #1 of the unicorn club: it was never sold at a billion-dollar valuation, at least as far as MoneyLemma can tell. Booted on a technicality. Here’s a harder one: Cargill, the Koch brother’s empire and America’s leading provider of grain and meat. Cargill’s revenue is highest in the US among private companies (15th overall). Parts of Cargill have been sold in the past, but the details aren’t public. What is public is that Cargill makes, in profit, over $3 billion per year. It’s hard to imagine Cargill isn’t a unicorn when it produces three unicorns in profit per year. Yet, there’s no evidence that Cargill has been sold at a unicorn valuation. Cargill therefore is and is not a unicorn; Schroedinger’s unicorn. There are likely a few thousand unicorns like this that won’t be on any list or radar. This is also why every unicorn list is different. Crunchbase (another unicorn-hunting research firm) has the current unicorn count at 820; CB Insights has it at 650. Different research firms have access to different data.

How is a unicorn made?

What better company to illustrate the creation of a mythical creature than Cirque Du Soleil?

The Montreal-based entertainment company describes itself as a contemporary circus. The formula here is roughly: traditional circus - animals + contortionists in neon leotards. Crank some deep house beats, layer in a plot that feels lifted out of a kid’s cereal commercial, and sell enough tickets to fill a stadium.

The first Cirque Du Soleil show was in 1984 when two Canadian street performers convinced the Quebec government to pay for a performance at a public festival (A.K.A. the Canadian Dream). That performance turned into the company’s first production, which eventually led to national, then international tours. This is an epic story captured really well on Company Insights YouTube channel. By 2015, Cirque Du Soleil was a sensation - over 100 million people had seen a show. They had residencies in Vegas and Disney World, Elvis and The Beatles themed shows. Still, Cirque Du Soleil was not a member of the unicorn club. It had never been sold, and therefore had no proof of admission. That changed in 2015 when co-founder Guy Lalibertè sold a majority stake of the company for $1.5 billion. The details aren’t public, but obviously the total valuation was greater than $1 billion, making Cirque du Soleil a unicorn at last!

The unicorn-industrial complex

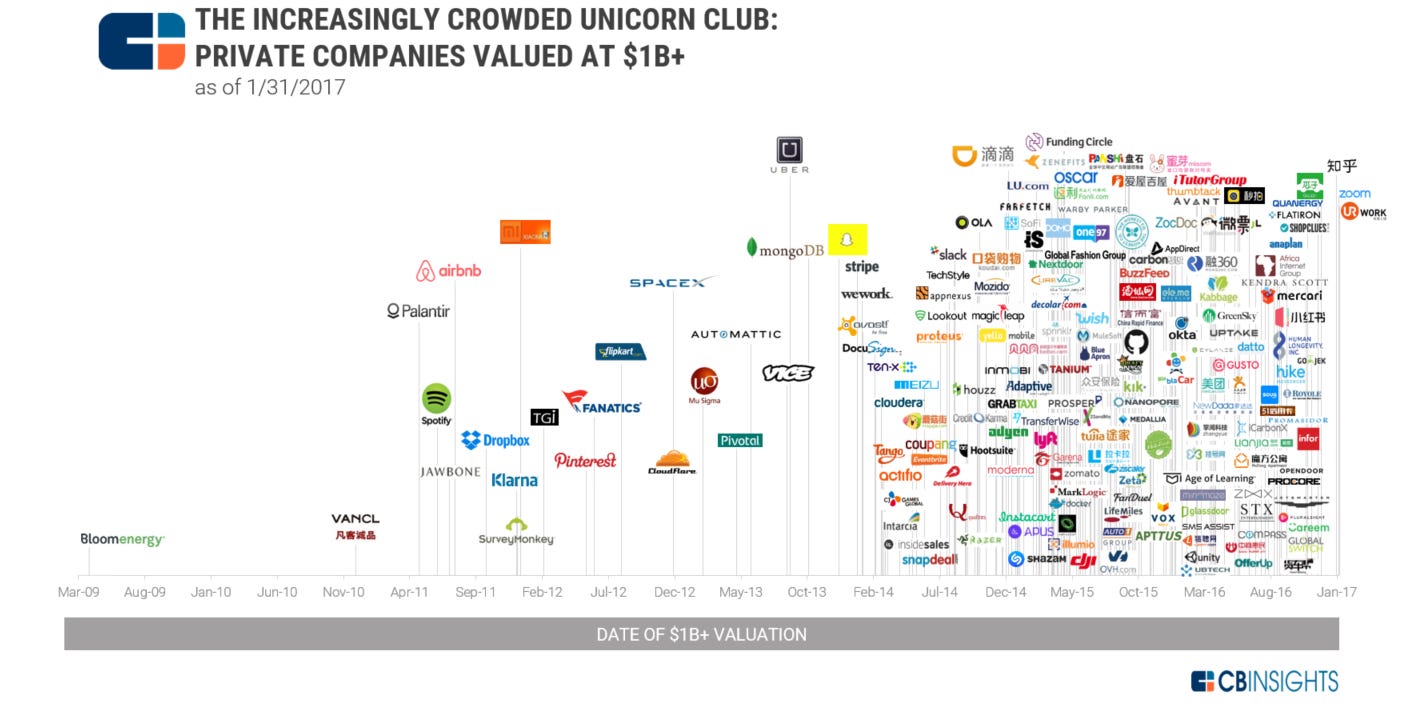

Here’s a chart of newly minted unicorns per year:

This chart captures a phenomenon unfolding in real time. Companies are launching and scaling quicker, driven in part by the unicorn-industrial complex. Venture capitalists, growth hackers, business incubators, Burning Man brainstorm sessions, cherub angel investors, self-promotional entrepreneur memoirs, cocksure ex-Googlers. All this and more make up the complex. It’s the unicorn factory, a Xanadu for capitalism.

Compare, as an example, the journey of scooter ride-share company Bird to that of Cirque Du Soleil. Former Uber/Lyft executive Travis VanderZanden saw an opportunity for scooters and launched Bird in September 2017 with $18 million in investor money. Within 7 months, Bird fundraised another $215 million dollars (in this case fundraise means selling a piece of the company and investing the proceeds back into the company). In its eighth month of existence, Bird fundraised another $150 million by selling a 15% stake at a $1 billion valuation, officially becoming a unicorn. A unicorn from scratch in just eight months! Bird’s short path to unicorn pastures was paved with investor money. Bird took hundreds of millions of dollars in investor money and amassed a great scooter armada, lobbied local city officials, bought silos of Soylent to sustain their software engineers. Cirque Du Soleil did it’s first round of fundraising when it was a 10-year old company - they sold a small stake to Fuji Television Networks for $40 million. Without massive cash injections, Cirque Du Soleil had to grow the old-fashioned way: slowly reinvesting profits into the business, growing day-by-day, like a clam sculpting a pearl. Cirque didn’t have the privilege afforded to Bird, which found its pearls by boiling the ocean with a 11-figure stovetop. Cargo containers of $100 bills weren’t heaped on Bird because it was a better business than Cirque - both are great businesses, most unicorns are. It’s just that Cirque Du Soleil was an ‘80s baby, born before the unicorn-industrial complex really got going (perfect timing for MTV though).

Unicorn factories are powered by money

Bird’s story (repeated many times) helps explain the burgeoning unicorn population. At first glance it seems that the unicorn-makers must be history’s greatest financiers. It’s beyond finance, actually, it’s alchemy, maybe even witchcraft - they turn mortal companies into mythical beasts. Reality, though, is a bit more subdued. The unicorn-industrial complex includes a vast, interconnected network of early-stage investors that are pied-pipers for investor dollars. Like a magnet near a wishing well, money flocks to the complex.

The unicorn-industrial complex promises investors that it will manufacture unicorns. Investors hand over their checkbooks. That money ultimately finds its way to young companies like Bird. As of May 2021, Bird has raised and spent $1.14 billion cumulatively. If Bird had just shut down the company and kept all the money it raised in a checking account, it would still be a unicorn today. It’s most recent valuation is $2.3 billion. That’s not bad, but it’s about the same amount that $1.14 billion would have earned over that period if invested in the S&P 500. There are a handful of investors that have some truly amazing success investing in early-stage companies, but many investors are investing dazzling sums with modest results.

Unicorn inflation: is this really a golden age?

According to Crunchbase, there were less than 5 new unicorns in 2006. There were 250 new unicorns in the first half of 2021.

That seems almost too good to be true, and it might be.

The most simple explanation of this growth is the one laid out above: new unicorns are genuinely good businesses scaling faster: the unicorn complex at work. Great investors finding great businesses and using investor money to boost growth. In this sense, the economy has become more efficient at allocating resources productively. Technology is a big part of this too: internet, software, capital markets, and the like are growth accelerants, elephants hanging from the feet of skydivers.

A second reason is the Bird phenomenon illustrated above. Some companies are receiving investments the size of a small country’s GDP. If a company that receives $1 billion in funding and then becomes a unicorn, that shouldn’t be surprising. A dumpster would be a unicorn if you filled it with $1 billion.

Third is that all the money pouring into early-stage companies has bid up valuations. This is classic bubble-behavior, what economists call irrational exuberance. Giddy unicorn-makers cutting checks at increasingly absurd prices, eyes glazed over as they stare toward the end of a rainbow. Oftentimes early-stage investors are accused of fabricating unicorns by purchasing small stakes of companies at unjustifiable valuations, thinking others will bid it up even higher (i.e., a speculative bubble). When they do this, they create unicorns, but those unicorns often go bust (for example the recently failed unicorn Quibi). In these situations unicorns are aptly named as they are imaginary. Or at least just regular business donkeys, a fleeting mirage fooling excitable would-be kingmakers.

Taming the unicorn

That covers the basics of the unicorn-industrial complex. If you’re hungry for more, here’s some good places to start:

A16z: One of the world’s top unicorn-makers, a16z is a venture capital firm that produces really great research on entrepreneurship and unicorn-building.

CB Insights: Unicorn leaders. They produce lots of great content on the unicorn-industrial-complex.

Sex & Startups (Zebras Unite): My all-time favorite opening line for an article. This is a great read on the satisfying diversity dynamics of Silicon Valley & Unicorn companies.

Crunchbase: Another unicorn-focused research firm. The link goes to their database, which lets you search the financial details of any company. The link goes to clubhouse, the audio-based social media app that recently became a unicorn.

How Venture Capitalists are Deforming Capitalism (Charles Duhigg, New Yorker): If you can’t tell from the title, this is hardly an unbiased piece. But a really interesting read that covers the WeWork story and venture capital’s role.