MoneyLemma: Healthcare

paying for the worst

It’s MoneyLemma Sunday! This post is about how much healthcare costs. Specifically, how much healthcare can cost in a worst case scenario.

America is the greatest place in the world to do this:

First of all, you get internet famous, promote a supplement, invest the proceeds in a laundromat, and have a reliable source of cash flow for life. Second of all, you have access to top-notch healthcare.

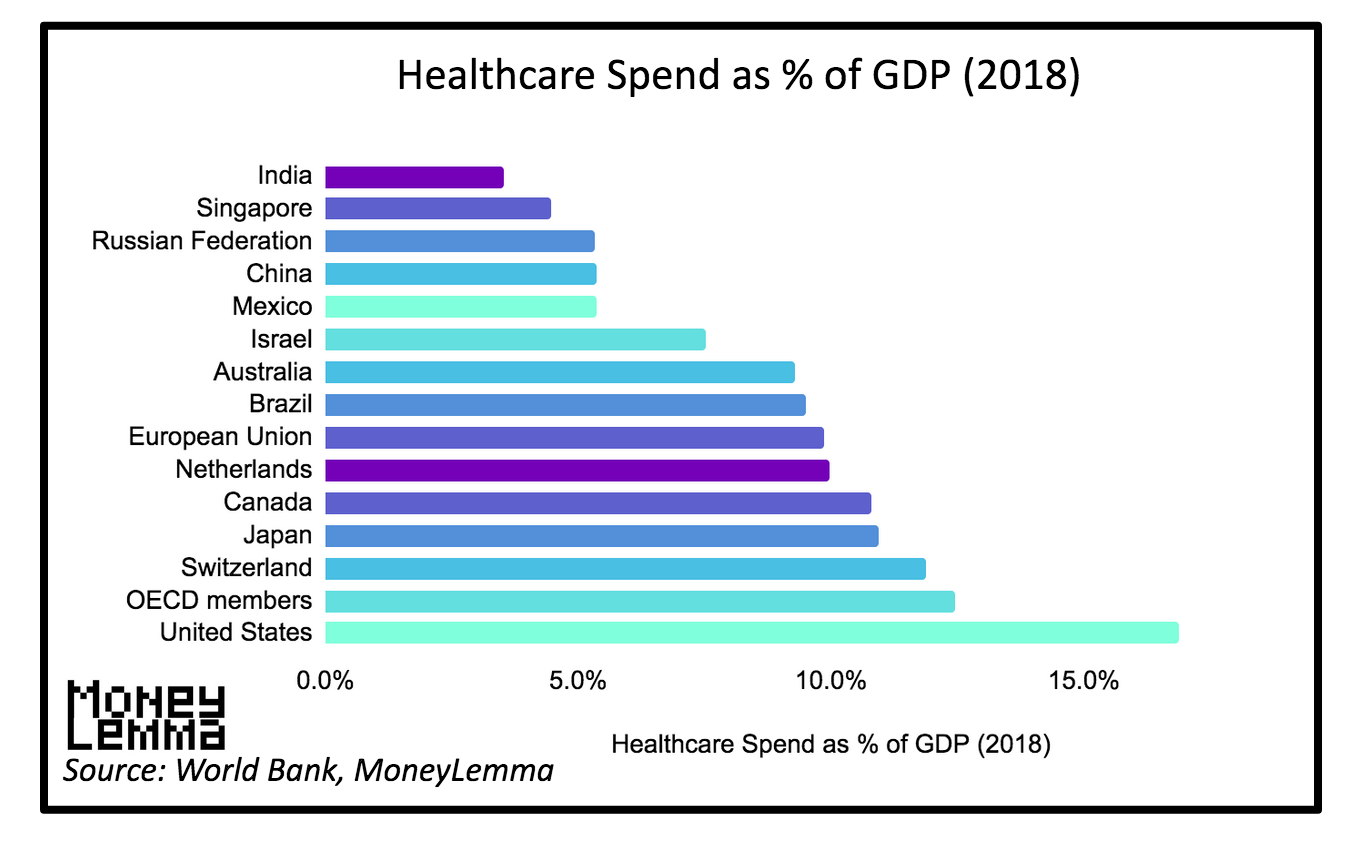

The downside is that American healthcare is expensive:

Americans spend $3.8 trillion on healthcare, or $11,500 on average (the typical household makes ~$70,000 per year after-tax). The challenge, though, is that average doesn’t mean shit. Some people spend $50,000 per year on healthcare, some people spend nothing. Very few people actually spend $11,500. Even when average costs are predictable, individual costs can be unpredictable. Most people would rather chew soggy sandpaper than plan their financial future because all these little uncertainties, when stretched across the canvas of a lifetime, amount to absolute chaos. How can anyone plan their financial future with the threat of a health crisis always lingering? We’re not all Walter White, we don’t have the AP Chem skills to cook meth anytime an unexpected bill comes due. The goal of today’s post is to understand the risks in healthcare spending: how much can healthcare cost?

Quick disclaimer on insurance

At the risk of stating the obvious, the worst case scenario is less worse with health insurance (at least, financially). Right now, 90% of Americans are insured. If that’s you, great, keep reading. If that’s not you, spend 10 minutes on Patient Advocate's website and understand your options right now (when healthy) and your options if something happens.

What is healthcare money spent on?

Here’s how healthcare funds are spent:

Hospitals and physicians clinics only take up half of the US healthcare budget. The other half is healthcare like elementary school nurses or senior living home orthodontists.

Who needs healthcare the most?

Health Services Research broke down lifetime healthcare consumption by age group:

No surprise, expected healthcare costs increase with age. One commonly quoted statistic says the majority of healthcare expenses are incurred within the last year of life. That’s not actually true. A Health Affairs metastudy found that around 10% of lifetime healthcare expenses are in the last 12 months. That paper argues that patients with chronic conditions are the biggest users of healthcare. In 2016 chronic conditions cost Americans $1.1 trillion, or 6% of GDP!

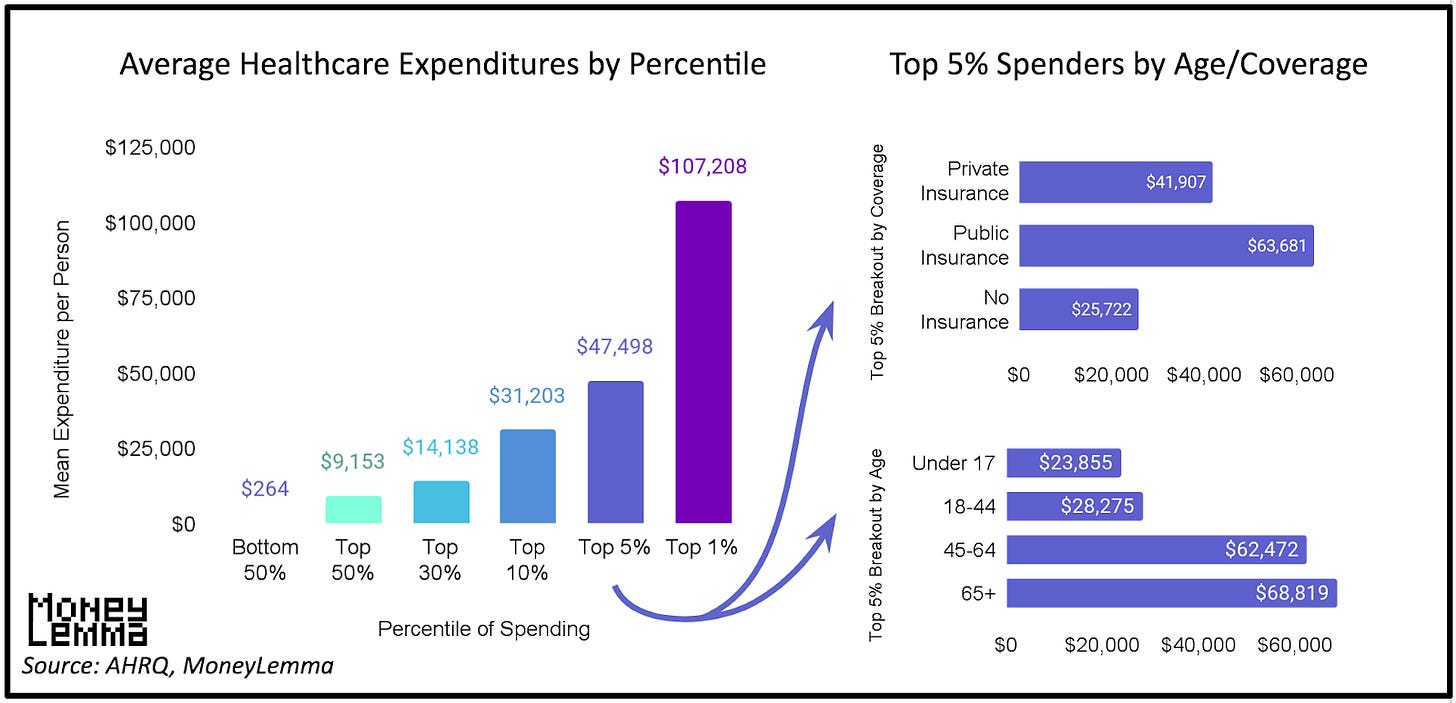

Here’s another way to think about the distribution of healthcare costs: most Americans are fortunate enough to consume very little healthcare in a given year, but those with serious health problems consume excessive amounts of healthcare. The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality estimates 5% of the population accounts for 50% of total healthcare expenditures.

What explains this phenomenon? Say you’re turning the corner of the frozen pizza aisle at Costco and a stray shopping cart clips you and tears your ACL (frankly, you’d be lucky to be alive after a run-in with one of those Wooly Mammoths on wheels). Within a month you have corrective surgery, but that’s not the end of it. For years there could be painkillers, follow-up doctor appointments, ice packs and heating pads, and physical therapy. All of these are separate incidents of healthcare consumption, but they aren’t independent. Statistically, healthcare consumption is a function of mostly dependent events, and that’s why costs tend to pile on for the unluckiest people. Research by the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) estimates that over 50% of people in the top quintile of spending in a given year will be in the top quintile the following year.

Who pays for the majority of healthcare?

Half of health expenditures are paid for by the government (with taxpayer money) and the rest by private individuals (either out-of-pocket or through their collective insurance payments).

There’s a lot of rhetoric about how healthcare should work in America, but it’s worth remembering that, in totality, there’s really no debate about who pays: it’s Americans funding their own healthcare. The debate is about how that burden should be distributed.

What’s the worst case financial scenario?

Let’s say something terrible happens to our friend Jeff:

What would Jeff have to pay in this situation? How likely is such an event to happen?

In a given year, 1% of Americans will incur injuries or diseases that cost at least $107,000 to treat. Total healthcare costs are technically unbounded, but let’s use $107,000 as a proxy for Jeff’s worst-case scenario. How much of that Jeff pays depends on his health insurance plan (if he has one), what hospital treated the injury, and other factors. Here’s a illustration of what Jeff would be responsible for under a basic insurance plan that has national average co-insurance, coverage, deductibles, and maximums (no need to worry about definitions to understand this chart):

With this insurance, $107,000 in medical expenses would cost Jeff ~$35,000. If Jeff doesn’t have insurance, Patient Advocate's explains how healthcare bills can be negotiated down or supported by taxpayer programs. Were this an episode of Grey’s Anatomy, Jeff would thank his sexy doctors and walk out of the hospital without a limp. Unfortunately, as discussed earlier, Jeff is likely going to continue to need high levels of healthcare for many years. The real worst-case scenario isn’t one year with a five-figure expense; it’s ten years of five-figure expenses. Not to mention that Jeff might not be able to hold onto his job as a freelance Grammarian given the health challenges (Jeff’s more detailed backstory is available upon request). At that point there are some grim options - he can declare bankruptcy, for example - but the fact is that a major health crisis can be a devastating financial burden (in addition to the shitty non-financial elements).

Preparing for the worst case scenario

Normally MoneyLemma’s personal finance posts conclude with the same message: understand the risks, understand yourself, make the best possible decision, then revisit that decision occasionally. That process works really well in most cases. Unfortunately, it doesn’t apply here.

A small group of really unlucky people consume most of the total healthcare of a population. Listeria (a foodborne illness) costs $116,250 to cure, according to a 2011 CDC study. 90% of national healthcare costs are distributed across large populations via insurance or government programs, but even the 10% that falls to the individual is unmanageable if the individual has bad luck. Just as there’s no way to prevent a major health crisis, there’s no way to budget for one either. The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services reports 21% of adult families with at least one child (and 9% of the total adult population) struggle to pay medical bills.

Half the population spends less than $250 per year on healthcare. For the segment of the population that does need financial support, newsletters can’t help, neither can credit-card cashback deals, 401-k employer matches, fewer Starbuck lattes or any of the other usual budgeting tips. There are two types of healthcare spenders - the lucky and the unlucky - and nobody knows which type they’ll be tomorrow.

Here’s my parting question to the reader: what is the best solution for managing the uneven distribution of healthcare consumption?

Sources

Health Affairs reports on end of life spending

Milken Institute studies costs of chronic diseases

NCBI: Great studies on health care consumption

Center for Medicare/Medicaid Services figures out who pays for healthcare