The curse of scale

why we never say enough

Scale is uniquely human. Whatever humans do, they figure out how to do more of it, how to do it at scale. Any animal could inadvertently invent Tupperware™, but what other species would go on to produce it in such libertine excess that the waste accumulates into a floating oceanic landmass big enough to hold all the gumbo in Louisiana? Monkeys have opposable thumbs but not Wiggles concerts or corporate retreats. Dolphins have high IQs but not city-states or international patent laws. Those things take scale. And to scale is human.

Scale is a problem-solver

The answer to why we humans scale is laid out perfectly by Yuval Noah Harari in Sapiens. We scale to solve problems. Always have, always will. Worried about a saber tooth tiger biting off your foot while you sleep? Scale from families into tribes. Want to have a steady supply of maize? Scale into a village that can support agriculture. Trying to have it all (peltskins, clay pots, cave paintings)? Try scaling into a town or a small city where you can have specialized craftspeople.

In a lot of ways every problem in human history has been solved by scale. Antibiotics, the printing press, the steam engine, pre-rolled joints - all these things were solutions to problems. They were also only possible because groups of people cooperated and pooled resources. Alexander Fleming discovered Penicillin, but such a discovery would be impossible if he had to forage for all his calories, build his own hut for shelter and stitch together leaves to cover his crotch like a Biblical Adam. Civilization climbed the first 10,000 stairs and Fleming took the final step. Human progress is scale.

Everybody get along or else

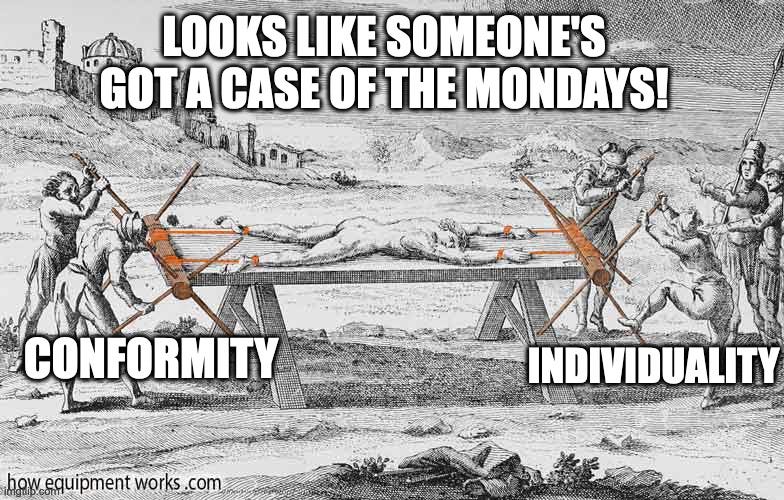

Scale requires cooperation. In small groups cooperating is relatively easy. In larger groups, it can be a nightmare. Waiting in line at the DMV, sitting for the SATs, navigating a shopping cart through Costco - all existentially dreadful. Civilization, the collective cooperation of everyone, is a tyrant who demands conformity above all else. One universality of modern life is the occasional weariness from that constant pressure to conform for the greater good. If life is one long stream of consciousness where you just do what you're told, then what’s the point? More importantly, civilization needs individuality. Progress is impossible without people who think differently - that’s how problems get solved. Fit in, stand out, fit in, stand out. Every pulsing minute the gears of cooperation and individuality crank in opposite directions. To the left, the sweet comforts of conforming; to the right, the freefalling ecstasy of individuality. We, the people, are pinned in the middle on a rusty sawhorse, a limb tied to each gear, stretched into skin-splitting agony.

This has forever been the great paradox of scale. Scale solves problems, scale causes pain. For as long as people have been around they have been scaling and also trying to resolve the misery of scaling. The social order of Confucius, Plato’s Republic, Marxism, The Declaration of Independence, The Chinese Communist Party, Burning Man pow-wows. What do all these things have in common? They’re trying to find a better way to organize people. A way to scale civilization while relieving the pain of scaling civilization. To scale is human, but to ail about scale…is also human.

In no place is this more evident than the business world. The innovator’s dilemma, coined by Clayton Christensen, describes the all-to-common phenomenon whereby companies stop being creative as they scale. As companies grow, the pressure to conform becomes overwhelming. Those who stick out get punished, so everybody clings to the status quo. That’s how Blockbuster gets toppled by Netflix, how Borders books gets toppled by Amazon. Loonshots, by Safi Bahcall, describes how some companies can defy the innovator’s dilemma by rewiring their incentives: find ways to reward individualistic thinking, even within a large organization. Of course, this isn’t really a business idea. That’s just another example of humans trying to relieve the pain of scaling through organizational design. Change the incentives, change the reporting structure, change the way new rules are made, change how rules are enforced. Keep changing until things get better.

Limits of scale are set by technology

But there are constraints on how much civilizations can change. Cooperation requires coordination, and coordination gets extremely complicated. Bigger-budget sequels are usually worse than the original for the same reason the Roman Empire collapsed under its own weight. Progress, scaling, it’s hard shit, and sometimes there are just limits. This is why people say socialism is a nice idea but doesn’t work - it’s just too hard to get the incentives right, too hard to scale civilization that way. But over time, those limits expand outward because humanity invents technology. New technology enables new types of civilizations. Modern democracy wouldn’t work before the printing press just as skyscrapers wouldn’t work without elevators.

Technology breaks its own boundaries

Technology, though, doesn’t just enable change, it causes it. Prior to the early 20th century, big wrap-around front porches were standard for American homes. People would sit outside and watch the world go by. When radios began appearing in American homes, people stopped sitting on porches and, probably, collectively realized how bored they’d been their whole lives. Around the same time, the average American home got a car. These two technologies changed the physical architecture of American homes - garages replaced porches. The interior of the home was redesigned to accommodate new technology as well: living rooms centered around radios, flooring designed for vacuum cleaners, kitchens redesigned for appliances. More than change homes, these inventions changed lifestyles. Automated appliances created more leisure time, recorded music allowed Elvis and his sinful, gyrating hips to become the first bona-fide rock star, and cars were the driving force of suburbanization. These changes bled into the broader social movements that defined post-war America. In this way, technology doesn’t just set the limits of scale - technology is an active agent of change.