What can we learn from business placebos?

quick thoughts on the placebo effect

MoneyLemma is widely considered [by this author] to be this century’s Dutch East India Company. That’s why we have a standing militia and an industrial warehouse of saltpeter. Does anybody need any saltpeter? Also, does anyone know how we can be granted sovereign waterway rights? If we get absolute power over just a single key trading route, then we’ll be a shoe-in for Y Combinator.

In his book “Alchemy,” Rory Sutherland tells the story of an airline that planned to invest billions of dollars in a new fleet. The airline’s passengers were miserable because their flights were always delayed and they had lost their sense of wonder at being able to literally fly. Right before executives signed an 9-figure check for all new planes, a wily ad-man, the ilk of Don Draper, stopped them. “What if” he suggested “we did nothing?” The airline executives were bewildered as the ad-man elaborated on his devious plot. The airline should put up big screens at every gate that updated passengers on potential delays in detail: what planes were behind schedule and by how many minutes. Don’t actually change anything, he was suggesting, just share the delay information. Airline leadership was skeptical but gave the idea a shot because, as corporate America executives, they are obligated to let overpaid consultants do their jobs for them. Sure enough, the screens worked. Passengers, almost instantaneously, became thrilled with the airline. It was the uncertainty, not the actual flight delays, that upset them all along.

For centuries the bland theories of crusty economists depended on the ideal rational person who carefully calculates every decision. Today we know the truth: people aren’t rational, at least not in an Age of Enlightenment sense. People are loaded with bias. In the case of the airline, the same person will have a better experience if there’s a TV screen telling them how late they’ll be. Same flight, same delay, same length of travel, happier customer. In other words, nothing changed, but things got better. There’s another name for that phenomenon: The Placebo Effect.

The Placebo Effect in medicine

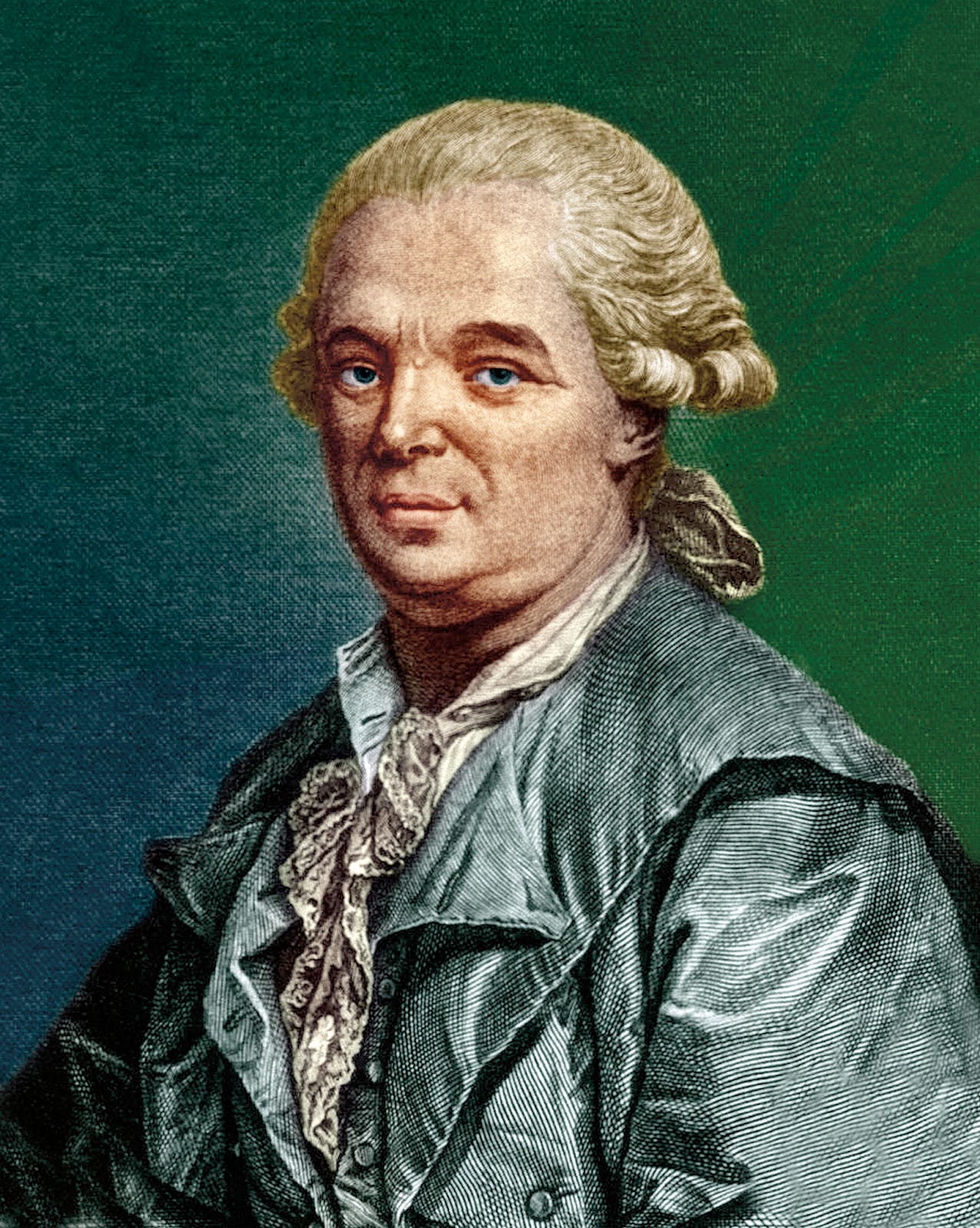

The Placebo Effect is nothing new. In 1784 an astronomer named Franz Mesmer was allegedly healing people using a combination of animal magnetism and electricity (I have no idea what that means). Louis XVI commissioned a committee of experts that exposed Mesmer as a fraud, and attributed any improvement in patient conditions to the Placebo Effect.

Mesmer definitely was a fraud, but that committee of irascible Frenchmen missed something important. And it’s the same thing scientists missed for centuries before and centuries after Mesmer: The fraud worked. I mean, it worked for Mesmer, but it also worked for the patients, at least a little bit. The Placebo Effect is generally dismissed as a sideshow - it’s not real medicine, not a real cure, not powerful enough to be taken seriously. Most people who find out they’ve been taking Placebos probably feel duped or ashamed, as if they were stupid to fall for such a thing. But in actuality, Placebos are a medical phenomenon, an understudied marvel. They do something without doing anything. Placebos can be a magical elixir, a wizard’s potion. Here’s Richard Dawkins (evolutionary biologist) and Nicholas Humphrey (Psychology Professor) explaining why science has been too quick to write off Placebos (they sound brilliant, but they do have British accents so who knows).

The business world generally takes much more than it receives from other disciplines. However, in this one regard, other sciences have something to learn from business: how to embrace the Placebo Effect.

Placebos in Business

The Placebo Effect, or rather, the art of creating value without doing anything, is Business 101. In business, we call placebos branding. Brands are the most supercharged power source in the universe. Slapping a Lululemon logo on polyester turns a $2 scrap of linen into a $120 pair of leggings. Bottling water or putting jewelry in a Tiffany box achieves the same thing. It’s alchemy. And sure, customers may only be paying for peace of mind or perceived quality or trust, but who cares? They believe and their belief creates value. Applying a logo to something doesn’t change the product, it’s just a stamp of approval. Like a doctor handing a patient a sugar pill. It does nothing. Yet, it does something.

Placebo is another way of saying the customer is always right. The customer thinks this shirt is more valuable if a little horsey is stitched on the breast? Then it is more valuable. The customer is willing to pay more if an overworked, underpaid senior citizen smiles at them when they walk into Walmart? Walmart will happily sacrifice an entire generation of elders for the cause. Call this shampoo all-natural, call this novel a classic, call this dilapidated shack a hidden gem. These things cost nothing but who is to say they do nothing? They make buyers happier, more confident, more secure. Isn’t that something? And if the Placebo Effect could make a patient feel better, even by way of a doctor slapping the medical equivalent of a logo on the patient’s forehead, then who's to say that’s not medicine?