the parking ticket industrial complex

If paul revere passed through a speed trap this nation wouldn't exits!

Why is the punishment for speeding a fine but the punishment for tax evasion prison? Which of the two is so dangerous that Agent Luke Hobbes is called in to apprehend serial offenders? And why is it that parking illegally is a ticket but ripping the tag off a mattress means prison, possibly a life term if I am to believe the warning on the tag? Loiter and you’ll be arrested. Idle, which is basically loitering with a car, and your wallet pays the price. Unless, of course, you are idling while in possession of contraband fireworks, anabolic steroids for which you have no prescription, or a species of endangered fish. In that case, straight to jail. We have two criminal justice systems, one for pedals and the other for bipedals. This whole conspiracy stinks worse than President Taft after a long, humid day of pheasant hunting.

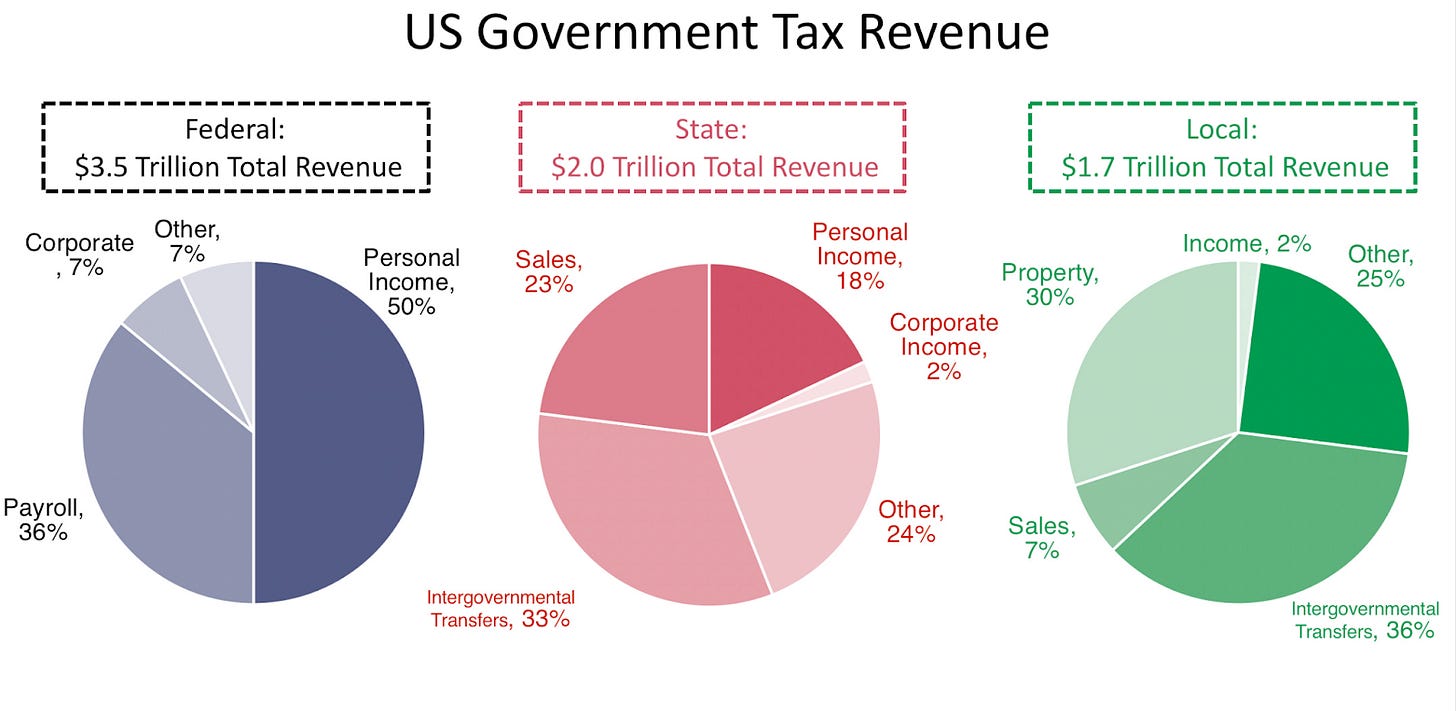

Follow the money. Fines and forfeitures together make up $16 billion in state and local government revenue annually, the majority coming from traffic violations.

While that’s less than 1% of the total revenue for those entities, it’s still important. The 1% figure is an average number and masks the fact that over 600 U.S. jurisdictions rely heavily (>10% of revenue) on fines for revenue.

In Chicago traffic tickets alone make up 7% of city revenue. Henderson, LA, a town of ~2,000, collected $1.7 million in speeding tickets in 2019. What’s more, traffic violation revenue can make up most (or all) of funding for specific agencies, often the police departments who issue the violations, a sure conflict of interest. But the economic problems of traffic tickets pale in comparison to the social ones: they serve as a regressive tax, they are systemically racist, and they’re dangerous. Also, and not to totally bury the lede here, traffic tickets are quite ineffective at curbing dangerous behavior. Most of the reduction in motorway deaths has come from technology and design improvements, not enforcement. Only the enforcement of DWI laws seems to have made roads safer in a meaningful way, and of course that’s one of the few traffic violations that is punishable with prison time, not just a fine. Putting all of this together, our traffic system is so indefensible even Johnnie Cochrane wouldn't take it on as a client. Surely this isn’t what our founding fathers intended. If Paul Revere got caught in a speed trap there might not even be an America! How did we get here?

A brief history of the traffic-industrial complex

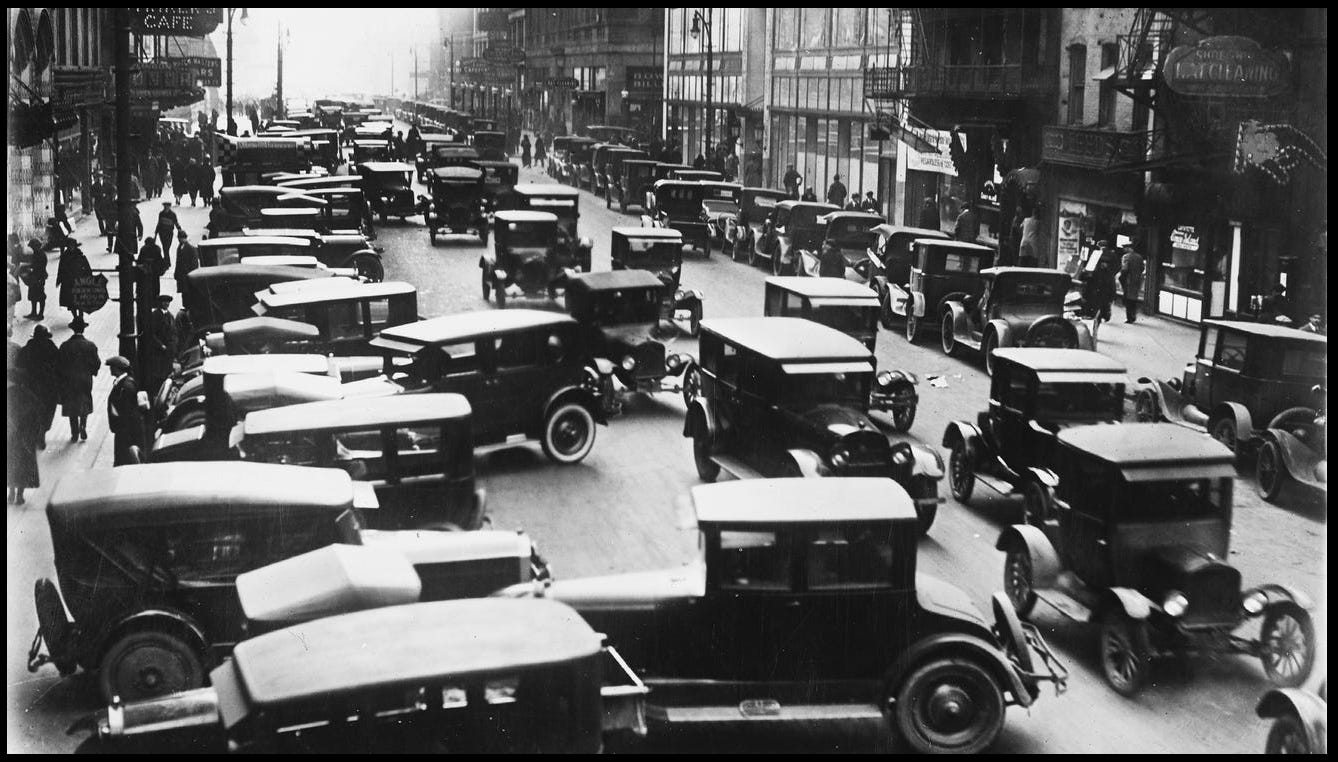

In the beginning there were no rules. The first automobile was invented by Carl Benz in 1886 but it was so expensive that even at the turn of the 20th century there were still just 0.1 cars per 1,000 people. In other words, so few cars that rules weren’t needed. And so a young Jay Gatsby might have been seen in his yellow Rolls-Royce, flappers dangling off the fender, careening around the bend of a treacherous mountain road, all without any worry of prosecution. The introduction of Ford’s mass-produced Model T marked the end of lawlessness. In 1909, its first year of production, the Model T sold about 10,000 units at a cost of $825 ($25,000 in current dollars). By 1921 the Model T sold over a million units for $300 a piece ($5,000 in today’s dollars). The Model T drove mass adoption of the automobile:

As more Americans bought cars, car problems piled up. Governments started passing road regulations, but this created a new problem: all the sudden, in a very short period of time, everyone in America became a criminal. Historian Sarah Seo explains (in this awesome podcast):

“An average town like Berkely, California had about half a dozen officers on their force. They didn’t have a lot of power to proactively investigate and go after crime and criminals and they mostly focused on the margins of society, like drunk people and vagrants…that was the state of policing before cars. Now after cars…police grew in numbers to dozens, even hundreds. And they got a lot more discretionary power and for the very first time they started enforcing the law against respectable citizens, citizen drivers [because] people were killing each other in their cars, there were so many traffic accidents. [As the traffic code became bigger] everybody became a misdemeanor offender and it was a huge problem. How do you get respectable citizens to obey traffic laws?”

The solution to this problem, and the answer to the question that opens this post, was to punish traffic offenders with small fines. That’s why vehicular crimes often don’t “count” as criminal offenses. If they did, we’d have to build a jail big enough to house the whole country. Administering these fines, Seo points out, meant expanding the size of police departments, which cost money, which, conveniently, fines provided. In this way, the invention of the Model T catalyzed a massive expansion of the American police force. However, this transformation happened very slowly. By mid-century there was a hodgepodge of state and local laws, but they were inconsistent and applied unevenly. Meanwhile, motor vehicle deaths continued to rise:

What really sped up the emergence of the modern day traffic-industrial complex was a raft of federal regulation in the 1960s and 1970s. Responding to both rising oil prices and the steadily increasing motor vehicle death rate, the government introduced the Federal Motor Vehicle Safety Standard, The National Highway Safety Act, the National Maximum Speed Limit Provision, and other regulations aimed at making driving safer, more fuel-efficient. Enforcing traffic laws was part of this structural reform. To get federal and state funding, communities had to start policing traffic. To this day, the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration provides $600 million to states each year, and those states send more money down to the local level. As you can imagine, this economic system supercharged traffic violations. Paying local governments to issue traffic tickets is like paying the Grinch to steal Christmas presents. The governments already get the money from the fine. There’s no need for more economic incentives, they come built-in!

These technological, economic, and legal changes manifested in our culture. To Americans cars have always symbolized freedom, but the type of freedom they symbolize has evolved. Until the 1970s, cars tapped into the endless frontier mentality - that pure, unbridled freedom of the road. The most popular 1970s movies and books about cars were “On the Road,” by Jack Kerouac, “Easy Rider” starring Jack Nicholason, “Two Lane Blacktop” starring Warren Oates or even George Lucas’ “American Grafitti.” In these movies, cars were a promise of limitless opportunity. But as regulation and enforcement of the rules of the road mounted, the car went from symbolizing a youthful, innocent freedom to outlaw freedom. More recent car movies like The Fast and the Furious, Gone in Sixty Seconds, and The Italian Job focus on criminal protagonists. In early movies cars were a tunnel to freedom, but now cars represent a propositional freedom that comes only at the expense of good standing in society. The meaning of this cultural shift is best explained by Department of Tranpsortation head John Volpe, one of the masterminds behind the modern road transport system. In an open letter to Motor Trend Magazine readers in 1973 Volpe wrote: “when you get on a public road, you surrender your private life and autonomous rights.” Today this statement seems obvious. To 1970s America this was a radical statement.The road didn’t mean surrendering your liberty, it meant seizing it! Volpe’s argument brings to the surface how a single technology can be both empowering and disenfranchising.

That’s how, if we trace traffic violations to its roots, we get a fascinating unfolding. A new technology (the mass-produced car) led to a structural change in our legal system (traffic laws, professionalization of police) which led to structural change in our economic system (road fines as government revenue) which led to cultural changes (technology and the nature of freedom). This topic truly is the overlap between our money and our world (hey, that’s the tagline for this blog!).

changing the system

The history of traffic tickets is a history of how sensible policy can lead to senseless political systems. It’s hard, almost impossible, to defend the traffic-industrial complex in its current state. It’s an illegitimate mechanism for supposedly democratic governments to extort their own citizens. The system is not transparent, it’s not fair, it incentivizes excessive and unnecessary traffic enforcement (like speed traps and ticket quotas) and it’s an overall waste of resources. Changing that system, though, will be a challenge. The political institutions that decide how to enforce traffic laws are reliant on the current system. It’s not as simple as voting in a new mayor who promises to make a change. There are thousands, maybe hundreds of thousands, of civil servants in this country whose salary is paid by fine revenue. The best way to begin to unwind the current system is piecewise. Start with a reduction in the federal highway grant money that is tied to traffic ticketing. Instead tie that money to outcomes, like reduced traffic fatalities.