Where is all the money in the world? (part 2)

Just when you thought this newsletter couldn’t get any sexier, we talk asset classes

Welcome all new MoneyLemma subscribers! Our numbers are growing, should we unionize?

This is the second of a two-part series on where all the money in the world is. Last week’s post establishes a definition for “money” and then sheds light on who controls the world’s money. This week is all about asset classes - the form that all this money takes

MoneyLemma’s last post established a definition for measuring wealth by adding up the world’s investable assets. The world contains hundreds of trillion of investable assets and most of those assets are owned directly or indirectly by individuals. This week’s post is all about what form those investable assets take. Although we (in America) measure investable assets in dollars, most investable assets aren’t literally dollars. They’re in the form of real estate, stocks, gold, bearskin pelts, Hartford Whalers sports memorabilia, pandemic toilet paper hoards, and much more.

A breakdown of the world’s investable assets

A long time ago this exercise would have been more of an adventure. Pirate ships filled with gold doubloons, enchanted woven baskets, towering bronze statues of muscular men, pots of leprechaun coins at the end of the rainbow. Did you ever hear of a Pharaoh who invested the royal treasury in a sensible annuity? Of course not, they spent all their money on cursed relics, built themselves awesome everlasting tombs, and slumbered with their wealth. People used to invest with their hearts, not their minds. Nowadays the world’s investable assets look depressingly rational:

Before we break down this chart, I want to reiterate something from last week: value fluctuates, making it difficult to pin down with accuracy. How do you value the vaults of the Vatican or the tomb of Mohammad? Order of magnitude is what matters. Last week we estimated that the total value of this pie was probably $200 to $500 trillion, depending on who measures and when they measure.

What the world’s investable assets tell us about building wealth

The rest of this post is going deeper into the makeup of the world’s investable assets. Where is the world’s valuable land? What is fixed income? Where does my Winklevoss-twins-signed ticket stub from 2011 Burning Man, priceless artifact that it is, fit into this pie? But first, an aside on cash-flow producing assets and wealth-building.

Over 90% of the world’s wealth comes from ownership of investable assets that produce cash flow. These assets can be “put to work” to generate a stream of income. Cows produce milk that can be sold for cash. Real estate can be rented out. Equity is legal ownership of the income that a business makes. Not all assets have cash flow. You can’t milk the Mona Lisa. A bottle of scotch recovered from the Titanic, a lock of JFK’s hair, a replica of the Constitution hanging in a museum because Nicholas Cage stole the original in order to save it from being stolen: all dope, undeniably so. However, the value of these artifacts is whatever someone will pay for it. These are speculative, not cash-flow-producing, assets. There’s absolutely nothing wrong with that. Many people make a fortune off speculation. Others just like to have mink coats worn by Miles Davis or ultra-rare Bordeaux vintages as a substitute for having a personality. Still, when it comes to wealth-building, cash-flow producing assets are the safest bet because they aren’t entirely dependent on what others will pay. Even if you can’t sell your chicken farm, you’ll most likely be able to sell the eggs it produces, and that creates a structural stability to your investment.

This is a good opportunity to think about what investable assets you own. Which ones produce cash-flow and which are speculative? You should have a good reason for owning speculative assets. Bitcoin is a great example. The price of Bitcoin is up a gazillion percent since it was created, but Bitcoin itself hasn’t really changed. People are just willing to pay more for it. To hold Bitcoin as an investment you should have clear reasoning for why people will continue to pay more for it. Many people do believe in Bitcoin and that’s totally fine. However, if you go through your portfolio and find it’s mostly speculative, then consider that you’re concentrating your resources in a category that excludes most of the world’s wealth. Do you have an expertise that justifies such a position? As you read the rest of the post consider what asset classes your wealth is in and whether those assets produce cash flow.

Back that asset up

Investable assets come in many shapes and sizes, so a taxonomy is necessary. Assets that share similar characteristics are usefully grouped together into classes, much like the animal kingdom or shitty country music. Within each asset class, there are subdivisions, sub-subdivisions, and divisions of those; asset classes peel apart like financial string cheese. For example, all the world’s currencies were listed as single group in the first pie chart, but can be split out:

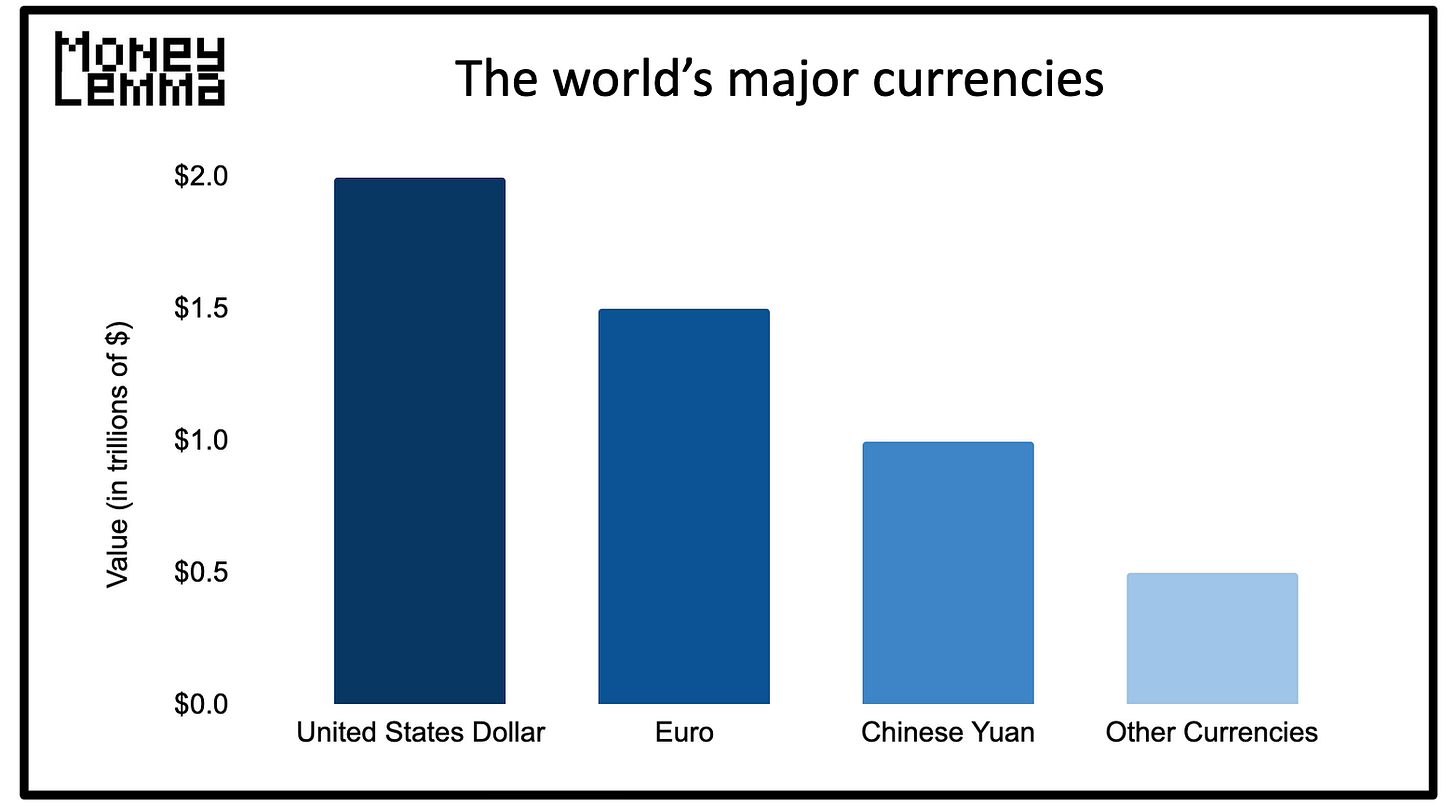

Likewise, Equity can be split into publicly-traded (Public Equity) or privately-traded (Private Equity). Venture Capital, investments in very early-stages of a company, are a subdivision of Private Equity. Seed investments, which are the initial investments into a company, are a subset of Venture. Most of these tedious sub-divisions are like red carpet award shows: excessive, meaningless, and created by self-important douchebags. Still, it’s worth spending some time going through each asset class at a high-level to understand what it is.

Appendix: breaking down the major asset classes

Real Estate: Real estate is the subset of the world’s land that is investable. Most of the world’s inhabitable land is real estate: from the Manson Family’s sun-soaked Los Angeles Ranch to the McCallister’s iconic Home Alone fortress (Zestimate for that house is $2,000,000), it’s all real estate. Excluded are places like Mt. Everest and Atlantis, should it exist. Not investable. We can further break real estate into residential, commercial, and agricultural:

Crammed ass-to-elbows the world’s population could fit inside the Parisian sewer network. People will pay for their space, though, and so residential is by far the biggest chunk of real estate. The world’s largest residential real estate market is China (30% of the world’s total according to Savills). Real estate in Shanghai costs about $2,000 per square foot, which is a bit below New York City, but Shanghai has 10x the landmass.

Commercial real estate, 10% of all real estate, is land designated for business-use by a government. This includes stadiums, skyscrapers, and all the world’s tourist traps: Madame Tussauds, Ripley’s Believe it or Not, Times Square restaurants, all 50 state capitals, any tall building that charges for a view, and most monuments.

Agricultural land is the last bit, and while it makes up half the world’s arable land it accounts for a fraction of the value. This makes perfect sense. It’s just golden soil from which the sweet sustenance of the world miraculously sprouts. It’s not like you can pave it and put up something useful like a parking lot. The world’s largest private agricultural landowner is Bill Gates, who in total owns a Hong-Kong-sized swath. He’s either trying to stop climate change or has some sort of sinister plan to corner the world’s celery market.

Equity: Equity represents ownership in a company. The bigger portion here is public equity, or companies that are listed on an exchange. Since these companies are publicly traded, we can actually calculate their value with precision: about $100 trillion. We can also break it up by country:

The other piece is privately held companies, including all the world’s startup unicorns, independent pizzerias, probably every Persian rug store, and all these vape shops that are clearly drug fronts. Over 99% of US businesses are privately held, but they generally are smaller than public companies. The Small Business Association estimated that public companies accounted for ⅔ of all company sales in America in 2007 (source).

Fixed Income: Fixed Income represents the loans outstanding to companies or individuals. People or entities who are owed money have an asset classified as fixed income. Different countries have different levels of debt. In some cases this is about access to debt - many poorer countries just don’t have banking systems that can reach the population. In other countries it’s purely cultural (people don’t like debt):

Currency: Cash is cash. Here’s a full breakdown of the world’s currencies:

Derivatives: Derivatives are financial instruments that derive their value from something else. Warren Buffett calls them “financial weapons of mass destruction” because they are complex, volatile and an unnecessary stockpile of them nearly wiped out civilization (in 2008 and probably a few times since that we don’t know about). In essence, though, derivatives are just contractual agreements that obligate one party to pay another if a predefined event occurs. For example, “You owe me $30 if it snows more than one inch in El Paso on November 4th 2024.” If you’re wondering what the difference between derivatives and gambling is, I can’t help you - ask an anthropologist.

Commodities: Commodities are raw materials, things that are stored in the earth. Oil, steel, coal, diamonds, elementary school time capsules. The ~$3 trillion figure used in this post is the value of commodities sold in a year because most of the world’s commodities are either deep in the ground or already included in other products (and therefore other asset classes). For example, the steel in a commercial truck owned by FedEx is included in the equity value of FedEx. The true value of the world’s commodities is many multiples of $3 trillion - the World Gold Council estimates that all the gold ever mined is worth about $8 trillion (and would fit in a three bedroom home). Global oil reserves (the amount of oil just sitting in barrels somewhere) are 1.7 trillion tons - that means that the 2020 crash in oil prices wiped out over $50 trillion in wealth.

Other Assets

Other assets cover any property where ownership rights can be transferred. That includes life-saving medication, autographed Nickelback vinyls, low-flying aircraft, rear view mirror objects that may be larger than they appear, and on and on. This category is almost impossible to value because nobody knows what’s in the private homes of the world. One thing is certain: it is growing. The category of Fine Art (ex. Starry Night or Beiber’s full-sleeve tattoo) more than doubled between 2008 and 2020, according to Artsy. Cryptocurrencies (also included in other assets) went from $0 in 2008 to $3 trillion today.